Phosphorus is a critically important nutrient, but it’s also a tricky one.

While phosphate fertilizer rates have been slowly increasing over the past few decades, crop removal has increased more. In fact, most prairie soils are at a net phosphorus deficit.

Building phosphorus reserves so our crops aren’t lacking this essential nutrient should be a part of every crop nutrition plan. But phosphorus deficiency is difficult to diagnose, making it a hidden hunger. Eliminating that hidden hunger is a wise investment for our crops and the productivity of our farm land.

Crop removal of phosphorus tends to exceed phosphate fertilizer application rates. Simply put, crops are removing more phosphate from the soil compared to the amount of phosphorus fertilizer applied. And it makes sense when thinking of the sensitivity of some crops to seed-row applied fertilizer. Safe seed-row rates tend to limit what we should be applying to match fertilizer additions with crop uptake and removal.

Role of phosphorus

Phosphorus is one of the 17 essential elements required for several plant functions, including photosynthesis. Its uptake is critical within the first four weeks of plant growth and if limited in those first weeks, a deficiency can lead to irreversible impaired growth later in the season.

Deficiency symptoms

In cereals, symptoms are typically non-specific, and are usually described as “poor growth,” “spindly plants” or “stunted stand.”

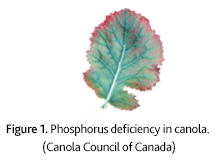

Sometimes symptoms are easier to recognize in broadleaf crops. In canola, for example, outer edges of leaves might appear purple (Figure 1). Other indicators of phosphorus deficiency include spindly plants and delayed maturity — often hard to discern without a check to compare.

Sometimes symptoms are easier to recognize in broadleaf crops. In canola, for example, outer edges of leaves might appear purple (Figure 1). Other indicators of phosphorus deficiency include spindly plants and delayed maturity — often hard to discern without a check to compare.

Soil levels and tests

The challenge with soil phosphorus is that it reacts readily with positively charged ions — called cations — such as calcium and magnesium under neutral to alkaline pH and iron and aluminum under acidic pH. The majority of prairie soils are neutral to alkaline so reaction with calcium and magnesium is common. Although a soil might have lots of phosphorus, it isn’t necessarily available to the plant. In fact, only about 10 to 30 per cent of applied phosphate fertilizer is used by a crop in the year of application. The remainder reacts with soil cations, becomes less soluble and is slowly available to the plant.

A soil test can help indicate the level of plant-available soil phosphorus. Generally, a phosphorus level of 10 parts per million — or 20 pounds in the top six inches of soil — is considered deficient. Ideally, a soil test level of 20 ppm would allow our soils to have a greater level of productivity. If a soil is deficient, research shows there’s a very high probability a crop will respond to phosphate fertilizer.

However, with limitations on how much seed-row phosphate can be safely applied, the problem is exacerbated.

Table 1: Balance between phosphate removal and recommended safe seed-row limits for seed-placed monoammonium phosphate in common prairies crops.

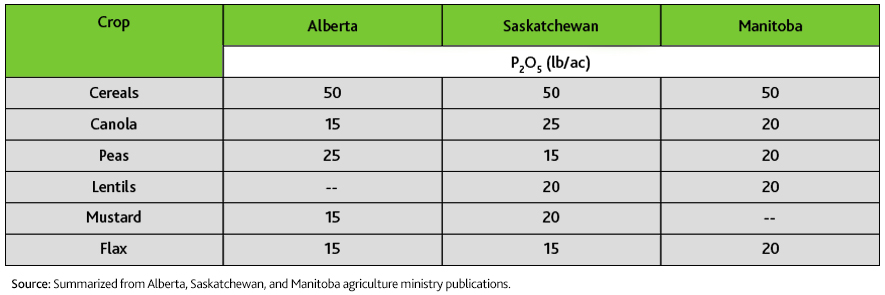

Safe rates of seed-row applied phosphate

Placement of phosphate is important. Phosphate is relatively immobile in soil (and remember, readily reacts with soil cations), so the first 15 lb of P2O5/ac should be seed-placed for greatest efficiency. In direct-seeded fields or early planted crops, where the soil hasn’t had a chance to warm, phosphorus mobility and uptake will be much slower, so seed placement is even more critical in these environments. It’s important to abide by the recommended safe seed-row rates so plant establishment isn’t put at risk (Table 2).

Table 2: Safe seed-placed rates of phosphate at 10 per cent SBU for various crops by province.

What can a grower do if more phosphate is required than the seed-row application allows?

Building phosphate reserves is a great strategy, especially when there’s evidence to suggest there’s more phosphorus being removed than applied. It’s easy to build reserves by including phosphate with nitrogen or other nutrients banded away from the seed row. Also, on years when cereals are seeded and higher seed-row rates can be applied, ensure application is at the maximum. An additional option is to include a phosphate solubilizing product such as Jumpstart® in the crop nutrition plan. A product such as Jumpstart can help release soil-bound phosphorus and make it more available to the plant.

A fundamental step in all crop nutrition plans is soil testing. Soil testing provides benchmark information on plant available nutrients. It’s a tool to help make more precise crop nutrition decisions. As the saying goes, “You can’t manage what you don’t measure.”

Knowledge & Innovation Manager